Willa Cather (1873-1947) is a complicated figure to talk about, in part because she guarded her privacy ferociously and threw roadblocks up in front of anyone who wanted to delve too deeply into her personal life.

Born in Back Creek Valley, Virginia, she was uprooted at the age of nine to live first in Webster County and then in Red Cloud, Nebraska, both of which, initially at least, she hated.

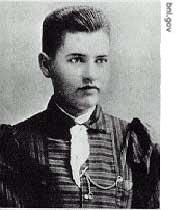

Good in school and a book-lover, Cather had a complicated girlhood, a part of which she devoted to being a boy.

She dressed in male clothing and insisted upon being called William.

Her neighbors probably found her behavior odd and may have shown it because Cather didn't stay in Nebraska any longer than she needed to.

As soon as she finished college, she headed East, to spend most of her life in Pittsburgh and New York City, returning home only for visits.

Still, it's the land of her childhood that became the inspiration for her two best novels,O Pioneers (1913) and My Ántonia (1918), both of which focus on immigrant families homesteading in Nebraska.

The heroines of both books—Ántonia Shimerda and Alexandra Bergson—are typical of the early Cather women. They are sturdy, hard-working, and passionate.

Emotionally tougher and spiritually stronger than the men who rely on and admire them, the women push themselves to the limits of endurance to take control of the land that always threatens to overwhelm them.

Cather's other famous heroine, Thea Kronberg, the central figure in Song of the Lark (1915), has left the farm behind. Still, she has the same fierce, single-minded drive of the other two women.

An opera singer, Thea will do whatever is necessary to take her place on the stage and in the spotlight, and Cather dwells on the hard, relentless training of Thea's profession.

Yet despite her celebration of powerful, ambitious women, Cather wasn't interested in anything resembling a feminist movement.

She was an individualist, who believed in the force of the passionate self, rather than the group, a fact which has endlessly troubled more politically minded critics, who want to see her work as a rebellion against some form of oppression.

As Joan Acocella points out in her lovely little book on Cather, Willa Cather & the Politics of Criticism, politically attuned critics are always finding "'gaps' or 'silences' or things not named—great holes in which, they decide, Cather is hiding something.

Then they tell us what the thing is: homosexuality, gender conflicts, American Indians...." [p. 78]

Perhaps Cather was hiding clues to her personal life or her politics in her books.

But who cares? The stories on the page—and they are wonderful, compelling stories—are all we need to know.