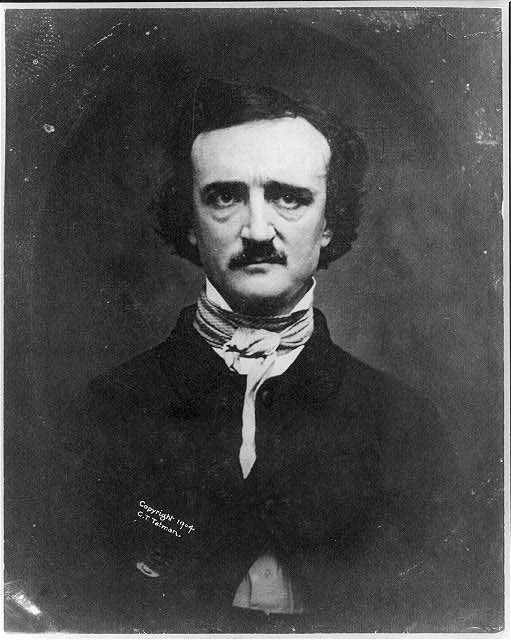

Image source: Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-10610

Author, poet, editor, and critic, Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 19, 1809. His parents were both actors, who died shortly after Poe's birth, leaving him to be raised by John Edward Allan, a well-to-do tobacco merchant, who never quite approved of his dreamy, poetry-writing foster child. Early on in life, Poe's gifts as a poet were recognized by his teachers, and by the age of eighteen he had published his first poem. It was called "Dreams," and in a way, it suggested Poe's life-long desire for a reality different from the one he lived. "Oh that my young life was a lasting dream....T'were better than the cold reality of waking life" he wrote. In the same year that "Dreams" was published, the young and very ambitious Poe also self-published his first book of poems, titled Tamerlane and other Poems. Poe is best known, though, for his tales of dark and macabre mysteries, in which he often focused on the twisted psychology of those who commit murder. In The Cask of Amontillado, for instance, the logical-sounding madman carefully explains how he hid his murderous intentions behind a cheery smile:

"It must be understood, that neither by word nor deed had I given Fortunato cause to doubt my good will. I continued, as was my wont, to smile in his face, and he did not perceive that my smile now was at the thought of his immolation."

Perhaps Poe's most famous mystery is "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841), in which he introduced the amateur investigator C. Auguste Dupin (Dupin reappears in later works as well). Poe's creation of Dupin, before the word "detective" even existed, is one of the reasons many people consider Poe to be the inventor of detective fiction, and Poe did indeed lay out the pattern for the modern crime novel, where the police fail to unravel the mystery and the amateur figures it out by following the clues. Poe was also the first American writer to try to earn a living from his writing, and for a while he almost succeeded. But luck turned against him. Plagued by money troubles, he died at the age of forty under fittingly mysterious circumstances. He was found lying unconscious in the streets of Baltimore and taken to a nearby hospital, where he died soon after.

Poe's biography was suggested by Vanessa Pulido of Long Beach City College, who also provided the basis for the passage shown above.